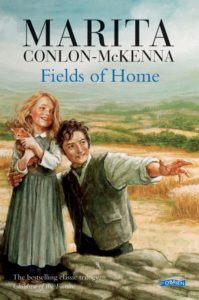

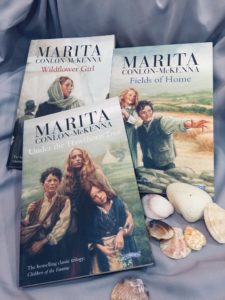

Fields of Home by Marita Conlon-McKenna is the third and final volume of the Children of the Famine trilogy. (I have reviewed the first two books, Under the Hawthorn Tree and Wildflower Girl.)

It has been twelve years since the Famine struck Ireland and the O’Driscoll siblings are now young adults and are still trying to build better lives. Eily and her husband have two children and are living on a farm with her great aunt, Nano. Michael is happily working in the stables in the Great House and is even riding in races. Peggy (I have such a spot for this lovely girl!) is still struggling to find her place and dreams in a land that hasn’t quite embraced her.

Ireland is in turmoil – rents are escalating for tenant farmers like Eily and her neighbours and the threat of eviction is ever looming. We see much of this through the eyes of Mary Brigid, Eily’s daughter – landlords are heartlessly throwing tenants out of the only homes they have ever known and like Mary Brigid, we worry and wonder where they will go and how they will manage. Michael, in training to be a horseman, loves his work, but his happiness is short-lived. He finds himself on his own again when the property where he works is sold following a fire. He has no place to go except back to Eily’s farm. The O’Driscolls must now rely on their ingenuity if they are to survive in post-famine Ireland.

Peggy, meanwhile in Boston, is acutely lonely – she is trapped in drudgery and her two friends are moving on. Kitty, her fellow maid, has moved on to serve in another house and Sarah, her beloved friend is moving West to better her health and prospects. James, Sarah’s brother, proposes to Peggy and asks her to come along. Despite her dire circumstances, Peggy is unwilling to settle and wants a true soul mate.

Peggy, meanwhile in Boston, is acutely lonely – she is trapped in drudgery and her two friends are moving on. Kitty, her fellow maid, has moved on to serve in another house and Sarah, her beloved friend is moving West to better her health and prospects. James, Sarah’s brother, proposes to Peggy and asks her to come along. Despite her dire circumstances, Peggy is unwilling to settle and wants a true soul mate.

You will find yourself rooting for these brave siblings. They are a tough lot – the kind who just grit their teeth and roll up their sleeves no matter what life throws at them. They are confronted with heartbreak and struggle at every turn and yet, even when they have barely anything to give, they reach out and help one another. This is what I found most heartwarming about this story – their undeniably strong love and their abundant hope.

This book may be for slightly older readers simply because the characters deal with more adult issues like politics, employment and marriage. My girls and I enjoyed the journey with the O’Driscolls and we formed such an attachment to the characters. This story ends on a beautiful note – there is finally the promise of better times!

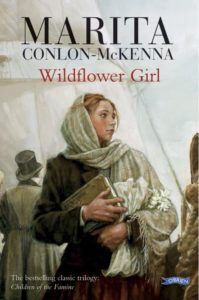

Peggy braves horrifying conditions on the month-long journey across the Atlantic. The poor passengers endure sea-sickness, cabin fever and wretchedly awful meals. Peggy survives this ordeal with the help of a friend, Sarah.

Peggy braves horrifying conditions on the month-long journey across the Atlantic. The poor passengers endure sea-sickness, cabin fever and wretchedly awful meals. Peggy survives this ordeal with the help of a friend, Sarah.

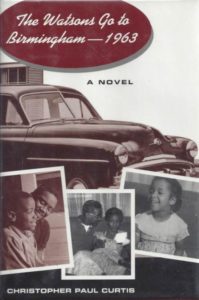

The family makes preparations for the trip like refurbishing the car and installing the Ultra Glide (a record player) to avoid country/hillbilly music.. Mom meticulously jotted dow nall rest stops and expenses carefully and precisely in her notebook entitled The Watsons Go To Birmingham – 1963. Dad however has other plans and saves money by driving practically non-stop.

The family makes preparations for the trip like refurbishing the car and installing the Ultra Glide (a record player) to avoid country/hillbilly music.. Mom meticulously jotted dow nall rest stops and expenses carefully and precisely in her notebook entitled The Watsons Go To Birmingham – 1963. Dad however has other plans and saves money by driving practically non-stop.

Armed with nothing but courage and love, they embark on a perilous journey across Ireland to find their great-aunts, Nano and Lena, whom they have only heard about in their mother’s stories. The children sleep in the open and forage for food in the wild and in the farms of dead tenants. They are confronted with death at every turn. They see bodies of those who died with no one to mourn or pray over them and they see the living dead – those so traumatised that they are but shells of their former selves.

Armed with nothing but courage and love, they embark on a perilous journey across Ireland to find their great-aunts, Nano and Lena, whom they have only heard about in their mother’s stories. The children sleep in the open and forage for food in the wild and in the farms of dead tenants. They are confronted with death at every turn. They see bodies of those who died with no one to mourn or pray over them and they see the living dead – those so traumatised that they are but shells of their former selves.